This post continues from the previous post: How Compressionists Think (1).

One of my favorite takes on AI comes from Ted Chiang’s 2023 essay, “ChatGPT is a Blurry JPEG of the Web (2023)”.

In it, Ted draws a clever analogy between ChatGPT’s hallucinations and the mistakes made by old Xerox photocopiers.

Those machines occasionally swapped letters or numbers in scanned documents — not because they were “broken”, but because of how their compression algorithm worked. To save space, the copier would merge shapes that looked similar, like confusing “8” for a “6”.

Ted further described ChatGPT as a compressed copy of all the entire internet — a single model that squeezes all the text on the Web into a surprisingly compact set of weights. We can “query” this compressed world using natural language, just as if we were searching the Web itself.

But of course, such extreme compression comes at a cost: artifacts. Just like the Xerox photocopiers that sometimes swapped numbers, ChatGPT occasionally hallucinates — generating details that sound plausible but aren’t actually real.

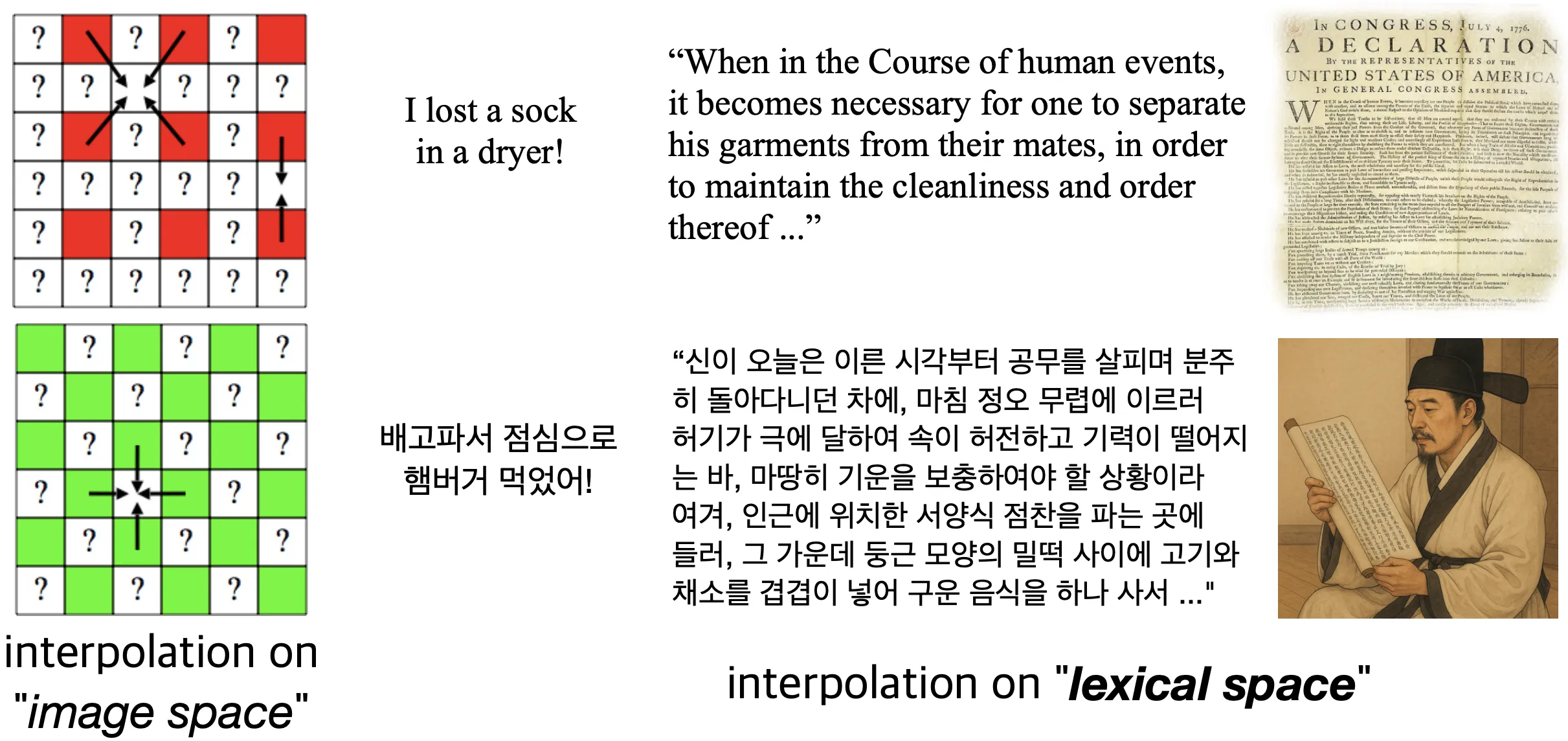

This analogy makes sense in many ways than it first appears. For instance, in image compression, algorithms often use interpolation to fill in missing pixels, and ChatGPT does something similar in “lexical space”: it predicts the most likely words that fit between others, performing a kind of linguistic interpolation.

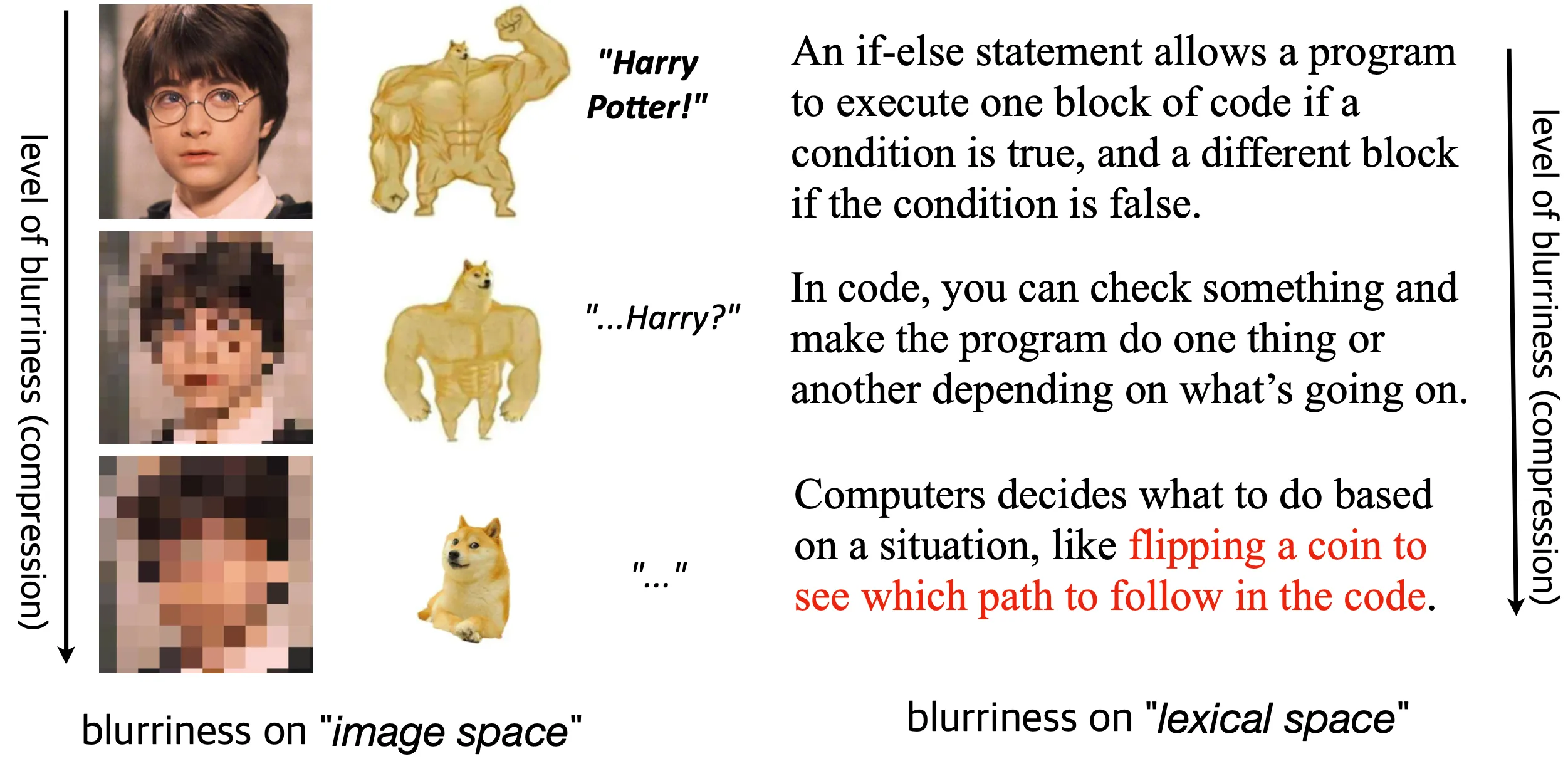

Another example would be “blurriness” defined on both image and lexical spaces. As compression level rises, one cannot accurately recognize the content of an image due to the loss of high-frequency details. We can observe similar phenomena from ChatGPT’s text generation, where the “blurriness” shows up as fuzzy facts or imprecise reasoning.

So yes, maybe large language models are just massive compression machines that occasionally pull out the wrong piece of information.

But… what does any of this have to do with intelligence?

Interestingly, a recent paper, Language Modeling is Compression (Delétang et al., ICLR 2024), dives into this question. The authors argue that a language model’s training function is, in fact, a compression objective.

This paper somehow explains how can something as simple as next-token prediction lead to the kind of intelligence we see in language models. For instance, language models are often trained only to guess the next word in a sentence but somehow end up being able to answer questions, reason, and explain concepts, which are not really trivial things we expect from the model to perform.

I find this perspective — seeing language modeling through the lens of compression — very fresh and interesting, and want to share my understanding on this a bit more. Before we dive in, let’s define some math notations to make things clear.

- A finite set of symbols

- A stream of data of length

- binary source code (compressor)

- The length of the compressed data using the binary source code

- A coding distribution

,

which follows the familiar chain rules:

We begin with Shannon’s Source Coding Theorem, which tells us that you can’t losslessly compress data to fewer bits than its entropy; i.e., the more regularities the data have, the better it can be compressed.

Using the terms we defined earlier, the theorem is written as:

where is the expected length of the bitsream and is the Shannon entropy.

Thus, for better compression, one needs to either hope for the entropy of the coding distribution to be small enough (which we cannot really control), or have the exact information of so that one can achieve the optimal compression.

In practice, we often model a probabilistic model to estimate the real target distribution , and instead can achieve a suboptimal code length .

In fact, this suboptimal code length is often termed, cross-entropy loss of the distribution relative to a distribution : , which is often used to measure how similar the estimation is to the actual distribution . If you look at the term carefully, you’ll see that needs to assign higher probabilities to the data likely to be frequently sampled from the target distribution , in order to lower the loss.

This means that the parameterized model can learn to resemble the distribution if trained under the cross-entropy loss objective, which in fact, is exactly how language model learns:

Above is often framed as “next-token prediction objective” in the context of machine learning.

Thus, as the model learns to predict the next token more accurately, it simultaneously learns to maximize the achievable level of compression.

Remember that being able to compress well could lead the model to understand things or make it intelligent, one can now roughly see how language models can answer so well to many questions that we ask them just by simply training on next-token prediction task.

Long before the actual language models are invented, Universal Intelligence: A Definition of Machine Intelligence (Legg & Hutter, 2007) already has pointed this out:

To see the connection to the Turing test, consider a compression test based on a very large corpus of dialogue. If a compressor could perform extremely well on such a test, this is mathematically equivalent to being able to determine which sentences are probable at a given point in a dialogue, and which are not.

Additionally, the in-context learning ability of language models is also explainable from this perspective: traditional compressors show higher compression ratio when encountered longer sequences, as they become able to exploit patterns and redundancy in the input sequence. This type of dynamical exploitation could explain the language model being able to better generate answers when given a proper in-context prompt, as the prompts allow them to better understand the data distribution they just have encountered and improve their compress-ability, or, intelligence.

So, if we can measure a machine’s intelligence level by its compress-ability, why don’t we evaluate LLM by making it compress things?

There are several attempts bringing this idea to language model.

- LLMZIP: Lossless Text Compression using Large Language Models (Valmeekam et al., arXiv 2023) actually uses LLM to compress English corpora.

- Kolmogorov Test: Compression by Code Generation (Yoran et al., ICLR 2025) suggests to evaluate model to create a shortest possible code that is able to generate the dataset (Code golf problem). Note that this code can be interpreted as another form of compression.

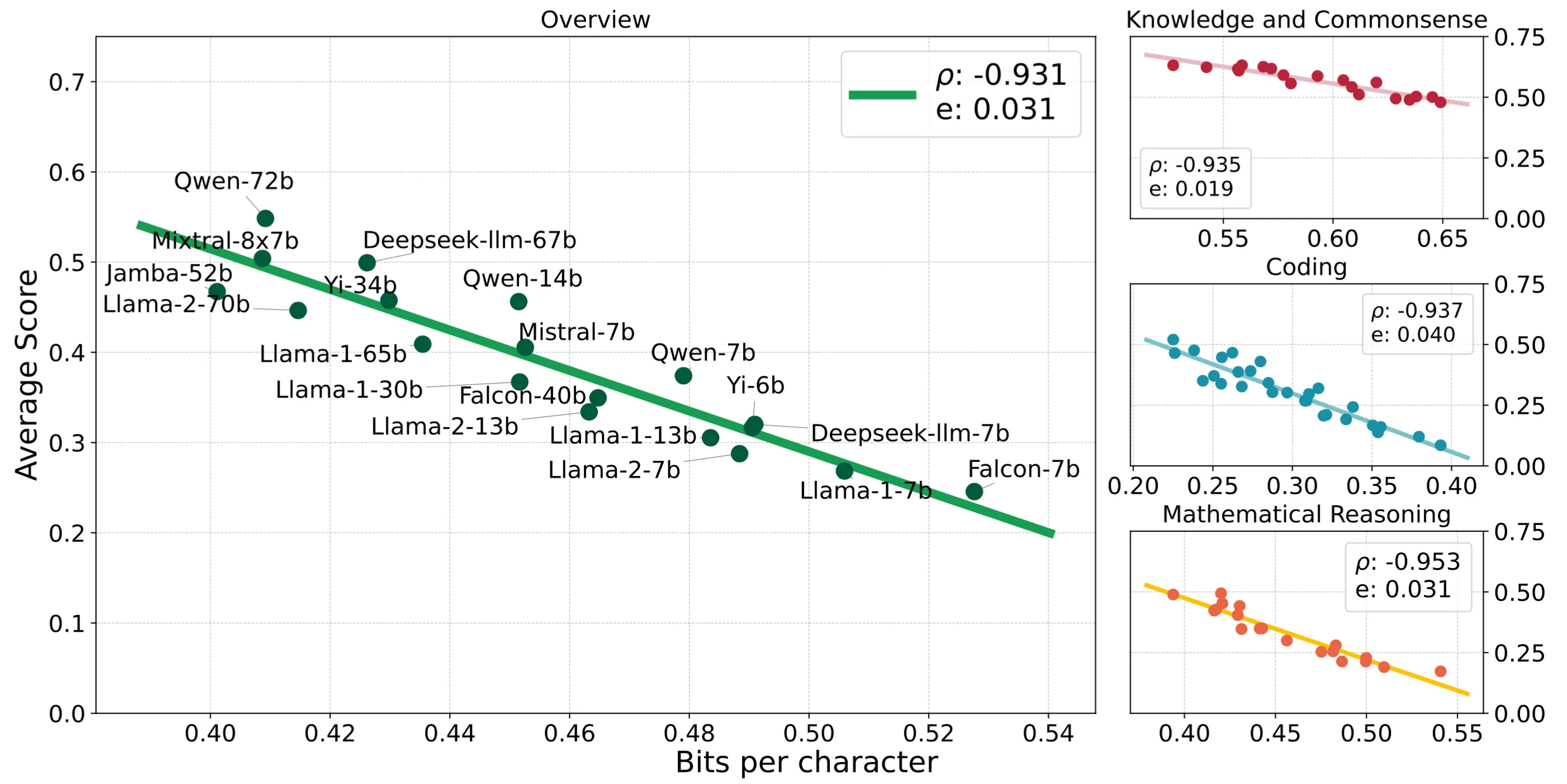

- Compression Represents Intelligence Linearly (Huang et al., COLM 2024) shows that the average of the numerous LLM benchmarks is linearly correlated to LLM’s compress-ability.

Figure 1 brought from the paper.

So far, we saw how language models are interpreted as compressors, and observe a close connection between compression and intelligence.

If a compress-ability can function as a quantitative measure for intelligence, would it be possible to train a model to become intelligent just by compressing?

In the next post, I’ll dive into a special case where a model actually develops intelligence purely by training under a compression objective — and interestingly, this one doesn’t even rely on next-token prediction.

.png)