In the early 1940s, as World War II raged across continents, another kind of war unfolded — an invisible one, fought not with bullets but with bits of information.

Both sides sought to intercept, encrypt, and predict each other’s moves through radio transmissions. In the middle of this information war stood Enigma, Germany’s encryption machine — mechanical marvel that turned ordinary text into unreadable cipher. It worked so well that Allied forces, despite intercepting countless German messages, were left staring at random codes.

Desperate for an edge, the Allies assembled a codebreaking team at Bletchley park, led by a brilliant mathematician Alan Turing.

After years of struggle, Turing’s team made a breakthrough: they noticed that many messages sent around 6 a.m. began with the word “Wetterbericht” (German for weather report), and many messages often ended with “Heil Hitler”.

By exploiting these small patterns and repetitions, they dramatically reduced the possible key configurations and finally broke Enigma.

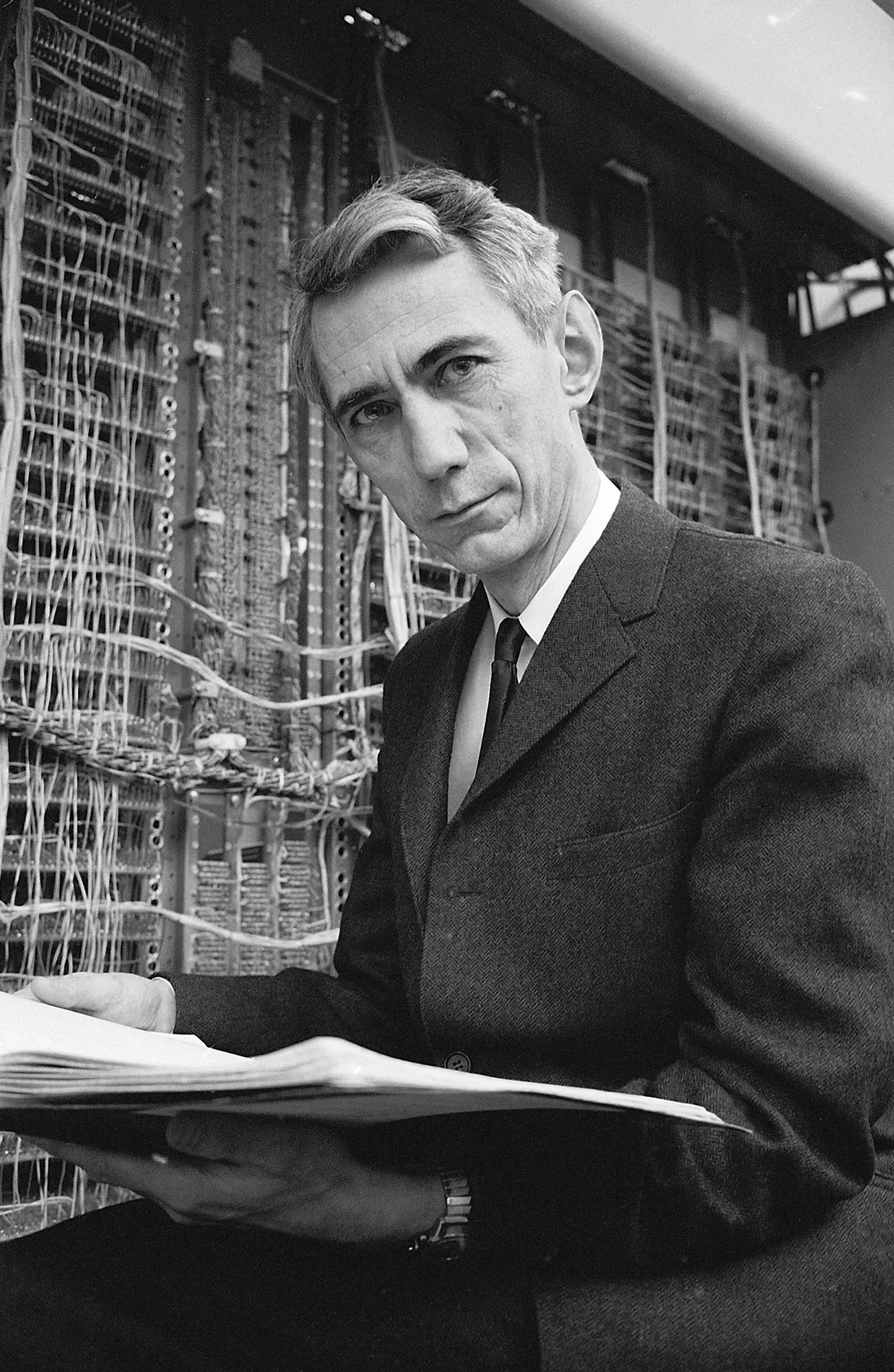

Claude Shannon’s perfect cipher

While Turing was decoding messages, there was another young mathematician, Claude Shannon, who was working on the opposite problem: how to make messages impossible to decode. As part of the Allied communications research at Bell Labs, Shannon developed the first mathematical theory of encryption. His classified wartime findings were later expanded to his 1948 paper, “A Mathematical Theory of Communication”.

In it, Shannon established a definition of a “perfect cipher” in a language of math. Specifically, he defined the process of cipher and decipher as the function between message space and code space :

For arbitrary and , Shannon insisted that a theoretically perfect encryption should satisfy:

which indicates that the probability of predicting the message should be equal to the probability of predicting it based on the information of : i.e., the encrypted message does not contribute to the prediction of the message , and thus, it indeed well-defines the perfect encryption.

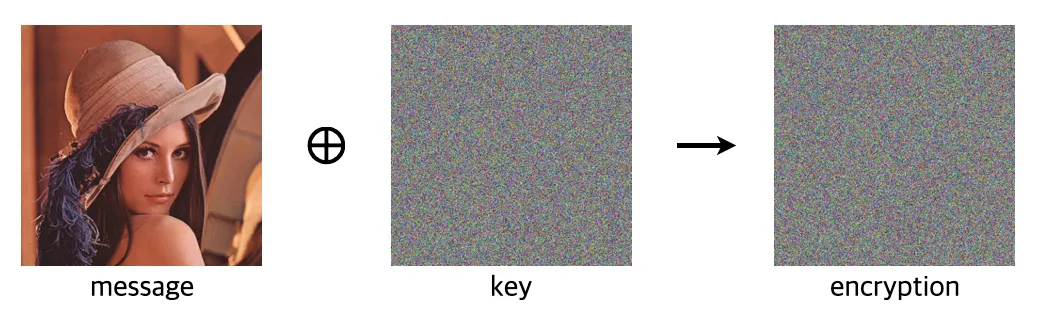

We can also say that the perfect cipher is one where the message and ciphertext are statistically independent—but is such encryption even possible?

Actually, the answer is yes.

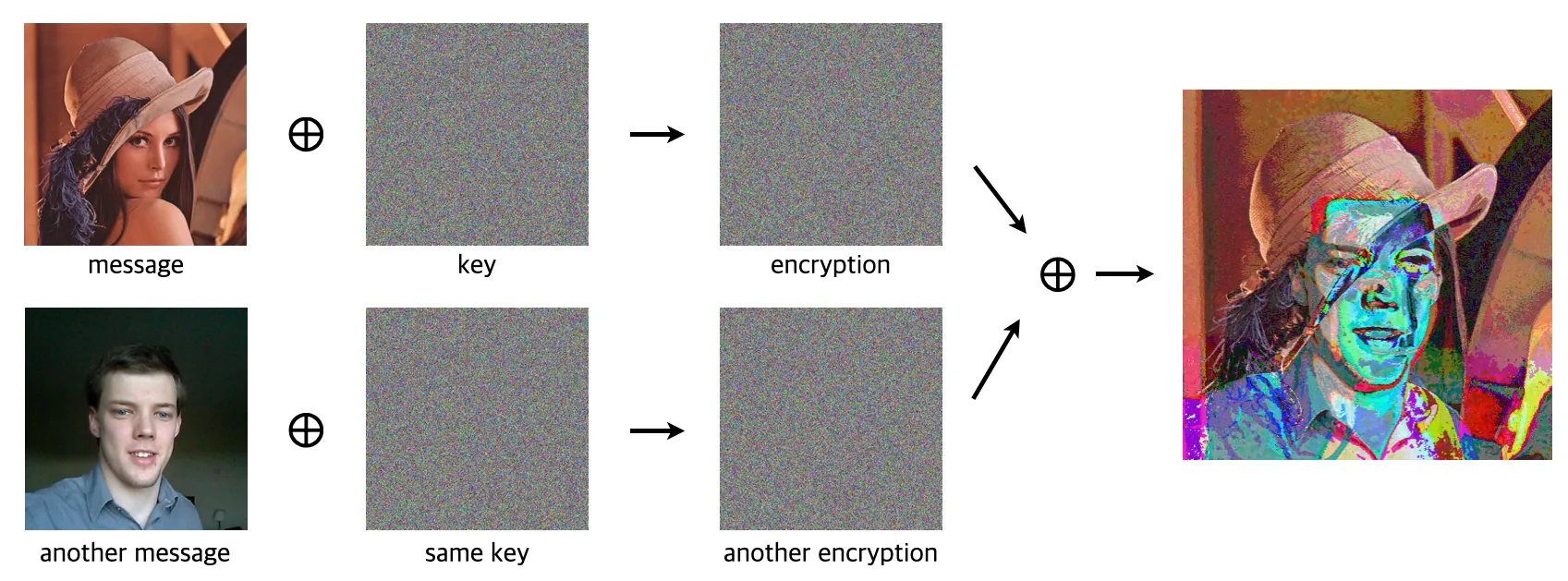

The one-time pad encryption achieves this ideal by pairing each message with a completely random key of the same length, combining them with an XOR operation. Because the key is truly random and used once, the ciphertext is indeed statistically independent to the original message. However, it is “one-time” for a reason: if the pad is reused, the encrypted message can be easily deciphered by using two encrypted messages that share the same pad.

Since carrying and protecting a unique key for every communication is almost impossible and inefficient, this type of encryption is not adopted in the real world.

In fact, such security and efficiency trade-off leads to an encryption inevitably carrying statistical regularities that the original message has: which means,

This implies that the understanding of a message can be acquired by finding these statistical regularities—redundancies, repetitions, patterns and structures—in the data, similar to how the encrypted code of Enigma was deciphered.

Here’s where compression comes in to explain its relation to intelligence: being able to compress well means that one is good at finding redundancies and repetitions, which in theory, should be an ultimate skill that is required to understand an unknown thing.

Compressionists

There is a group of people who call themselves “compressionists”, as they believe that studying compression will eventually lead to intelligence.

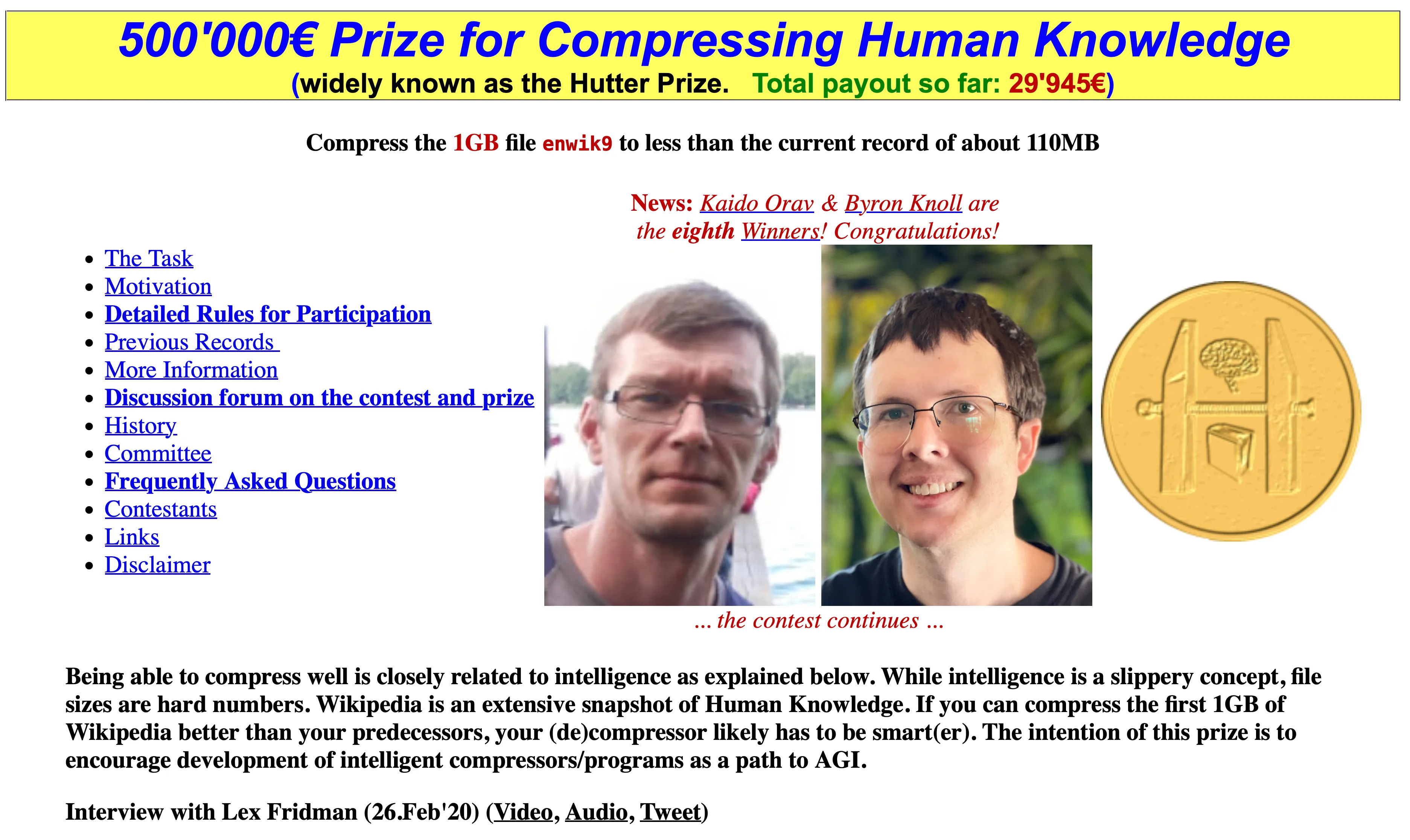

One of their known activities is “Hutter Prize”: they are giving a grand prize to the person who losslessly compresses the 1GB file of wikipedia into the smallest file size.

The name of the prize was named after Marcus Hutter, who is known for being the author of Universal Intelligence: A Definition of Machine Intelligence (Legg & Hutter, 2007). In this paper, the authors mention “compression test” as a way to measure machine intelligence.

Compression tests. Mahoney has proposed a particularly simple solution to the binary pass or fail problem with the Turing test: Replace the Turing test with a text compression test [Mah99].

Note that all data we perceive and generate are something that is not very friendly to machines: it’ll be like us seeing encrypted codes generated by Enigma. By letting machines to find statistical regularities inside, they might be able to understand human-friendly data just like how Enigma messages were decoded by humans.

And interestingly, this process of “finding regularities” is, at its core, a form of compression.

So, how exactly does compression lead to intelligence?

There are some fascinating examples that show how it works, which we’ll explore in the next posts.

.png)